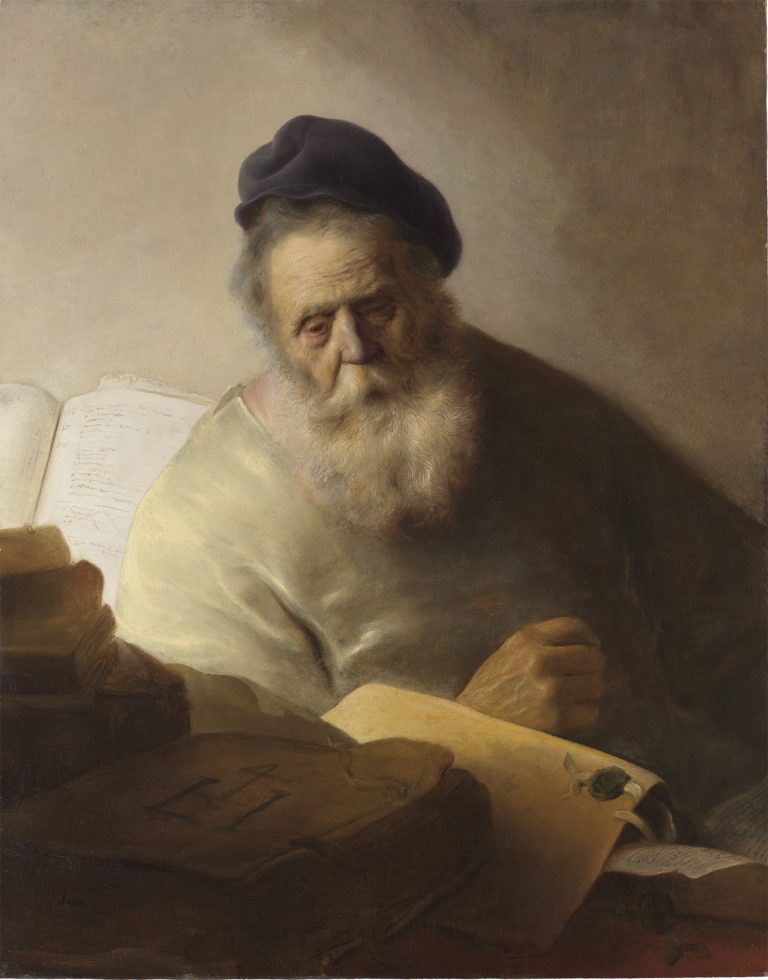

Seated at his desk amidst a stack of books and notarized documents, an old man focuses on a page propped up by a book as intense light falling from the upper left casts a dramatic play of light and shadow over the scene. Light provides the expressive means by which Jan Lievens has created a series of powerful opposites, for example the brightness of the white pages of the book in the background versus the darkness of foreground stack of books, or the radiant lemon-yellow of the sunlit portion of the man’s cloak as opposed to the deep grays of its shaded right shoulder and arm. Such chiaroscuro effects also play out on the man’s face, where pinkish folds around the man’s left eye and cheek give way to deep shadows on its opposite side. Light also accentuates the wrinkles in his forehead and picks out the long strands of hair in his beard and mustache.

One could imagine that Constantijn Huygens had a painting such as this in mind when, after visiting the artist’s studio in or around 1628, he praised Jan Lievens for his audacious themes and forms and for his extraordinary ability to depict the human face.1 Indeed, the present work typifies Lievens’s bold handling of paint while exemplifying his ability to capture the physical and emotional states of his subjects. The sitter’s remarkable physiognomy is achieved through a wide variety of brushstrokes that define his network of wrinkles and sagging folds and frame his face with a soft mane of tousled hair. The old man’s downcast eyes are bloodshot and betray a lapsing focus, implying that he has spent many hours doing mental work. A sense of elapsed time is further suggested by the position of the old man’s black cap, which is tipped to the back of his head as though a stretch and a sigh have just transpired, signaling the end of a full day’s work.

Huygens also remarked that the artist’s brimming self-assurance led him to work in a scale larger than life. Indeed, the present work relates to a number of other half-length single figures executed in the artist’s ambitious scale. Many of these portray elder wise men in the guise of apostles or evangelists surrounded by tattered manuscripts and books, and show them reading, contemplating, or in the act of writing.2 The type of books and documents on the desk and leaning against the wall, which show numbers and canceled notations, suggests that the man in this painting is a bookkeeper or an accountant. The prominent book in the foreground containing the merchant’s mark “LI” with the numeral 4, identifies the book as a ledger.3

This painting relates thematically and compositionally to Lievens’s The Pen Cutter, now on loan at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum from the Sal. Oppenheim Collection (fig 1). This work similarly features a single figure seated at a desk surrounded by books and documents, but shows the man in the act of sharpening a quill, with an hourglass and moneybags on his desk. This painting has generally been dated to ca. 1627 on the basis of its close thematic connection to Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Goldweigher, dated 1627 (fig 2).4 It seems probable that Bookkeeper at His Desk was painted at approximately the same time, ca. 1627.5

Lievens employed an expressive technique of incising into the wet paint with the back of the brush to emphasize the wiry texture of the old man’s hair. By using highlights and lowlights that create a contrasting network of hair, Lievens evoked a sense of depth and movement. This technique, which Rembrandt and Lievens both used in the mid- to late 1620s and which perhaps derived from their early efforts in etching, is indicative of their close collaboration and the shared continuum of their ideas. Lievens’s treatment of the sitter’s beard in the present work is also consistent with his work in etching and chalk, as in his red chalk drawing in Darmstadt, A Bearded Old Man with a Book (fig 3). The similarity of the sitter’s position with regard to the picture plane, emphasizing the oblique angle of the man’s head and the diagonal lines in the composition, suggests the sketch may have served as an early study for the figure in this painting.

X-radiographs reveal an earlier composition beneath this image. Oriented upside down, it depicts a three-quarter-length portrait of a man in a hat with a lace ruff (fig 4). Dendrochronological data indicates the earliest use of the panel from 1603 onward, leaving a period of around two decades during which the portrait could be dated.6 The style of this underlying portrait is unlike anything Lievens is known to have painted in his early years and must have been painted by another hand. Lievens is known to have acquired inexpensive panels during his Leiden years, and this previously used panel may have been one of those.7