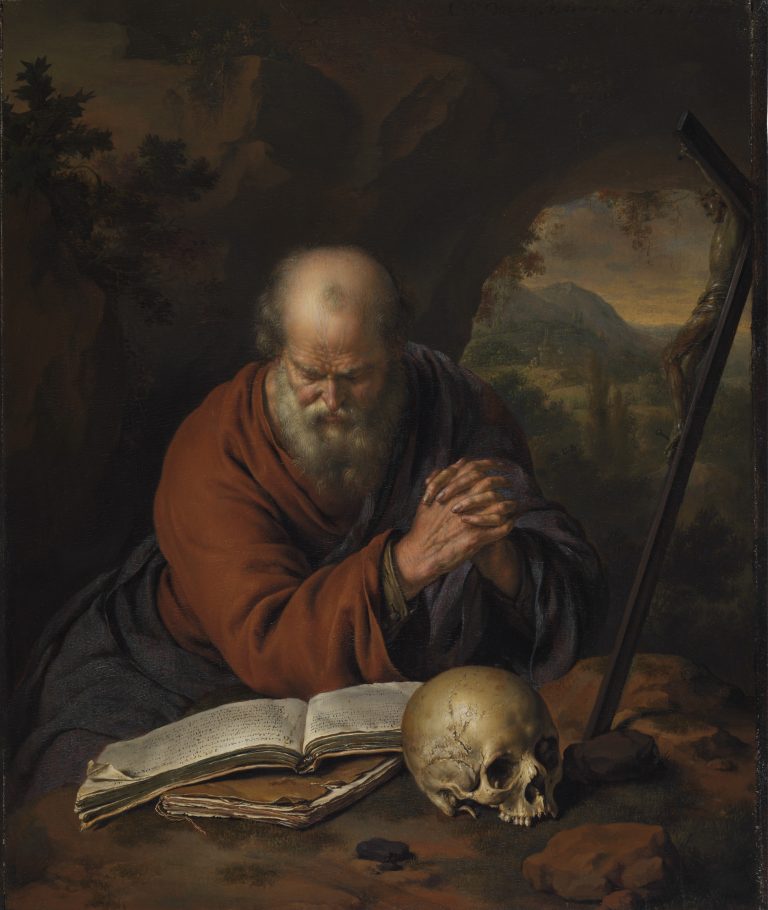

An old hermit, tucked away in a rocky cave opening to a mountainous landscape, clasps his hands in prayer as he bends over a stone table, upon which rest two books, a skull and a crucifix. He gazes downward upon the open pages of one of the books, his eyes almost closed as he concentrates inwardly on the meaning of the text. Light falling from the upper left separates the bearded hermit from the darkness of the grotto, and creates tiny, shimmering highlights on the sculpted figure of Christ on the wooden crucifix.

The religious character of the image might lead to the assumption that the painting was destined for a Catholic patron, but the subject of a religious recluse was not uncommon in the Protestant culture of the Netherlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.1 One hermit that appears in a number of Dutch paintings is Saint Jerome, the leading translator of the Bible.2 Although Willem van Mieris did not include Saint Jerome’s attributes of a lion and a pen, he may well have had this hermit in mind when conceiving this work. A sales catalogue from 1747—the earliest known record of this picture—identifies the painting as “St. Jerome in a cell.” This catalogue also notes that the painting had a pendant, Mary Magdalene, by the same master, a painting that can be identified as The Repentant Mary Magdalene of 1709 (fig 1).3 In this painting, Mary Magdalene sits with her attributes in a similarly craggy landscape. She also turns her head and upper body to look at a crucifix on her right in such a manner that visually connects her to the hermit in the present picture.4

As one of the most esteemed successors to the seventeenth-century painter Gerrit Dou (1613–75), Van Mieris often adapted subjects and motifs from Dou’s pictures. The present painting is no exception.5 At least eleven pictures by Dou feature hermits. The Hermit of 1670 (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), for instance, depicts the same type of old man before a Bible, a crucifix, a skull, a basket, and an hourglass on a stone table.6 In his picture, Van Mieris clearly carried on Dou’s pictorial tradition. He also strove to emulate Dou’s refined painterly technique of differentiating surfaces in his figures and still-life objects. The delicately executed and minute details of the still life on the rock and the old man’s head and hands—especially the wrinkled forehead with the bulging veins, the long gray beard, and the rugged hands with black fingernails—demonstrate Van Mieris’s utmost effort to display his virtuosity as a “fine painter.”

The great reputation of Dou’s hermit paintings among early eighteenth-century collectors must have been one of the factors that determined Van Mieris’s choice of the subject.7 For instance, the artist’s chief patron in Leiden, the illustrious collector Pieter de la Court van der Voort, bought one of Dou’s hermits from another elite Leiden collector for the enormous amount of 3,000 guilders in 1710.8 It thus comes as no surprise that Van Mieris chose this subject to parade his virtuosic technique as he sought to appeal to the art lovers of his day.