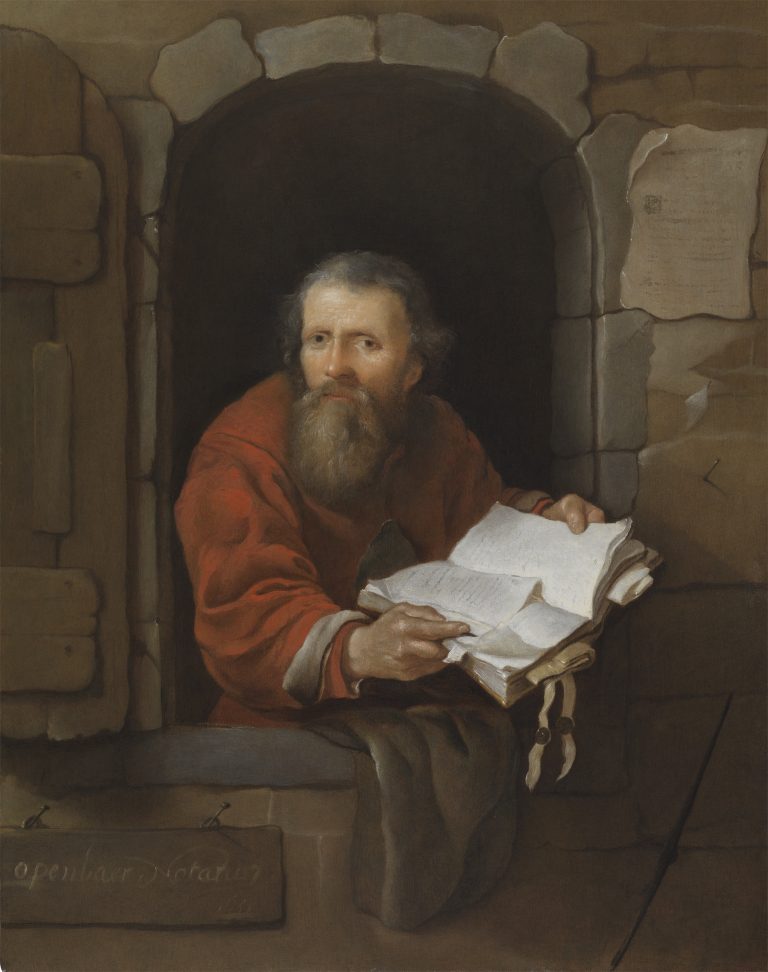

An old man with a full gray beard and wearing a red cloak stares directly at the viewer as he leans out of an arched window set into a brownish-gray stone building. His large, boney hands hold open a folio containing a number of loose sheets of paper, as well as an official document with attached wax seals. On the wooden sign hanging below the open shutter is an inscription that reads openbaer Notarus (public notary). The sign also bears the year in which Gabriel Metsu completed the picture, one of only fourteen extant paintings that are dated.1 Unfortunately, the last digit is almost illegible and cannot be clearly read.

Given the painting’s stylistic similarities to Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery in the Musée du Louvre, 1653 (fig 1), it seems probable that Metsu executed this work in the same year.2 The Louvre painting is a large biblical scene on canvas, rather than a single-figure painting on panel, but it has a comparable palette consisting of brownish-gray colors combined with distinct areas of red and white. Moreover, the facial type and posture of the notary with his raised shoulders is identical to that of the central Pharisee. Finally, the two paintings include finely executed large folios, documents and seals similar to those that appear in other of Metsu’s works from around 1653–54, including another depiction of the same notary and Woman Reading a Book by a Window (GM-105).3

Public Notary dates from the early period of Metsu’s career when he was active in his native Leiden. During these years he painted mostly on large canvases, depicting subjects drawn from the bible and mythology such as in the Louvre painting, or from farcical literature and popular culture. The small scale and panel support of Public Notary are quite exceptional, and this work seems to be the first instance in which Metsu responded to the work of Gerrit Dou (1613–75).

Metsu’s prime source of inspiration seems to have been Dou’s A Painter with a Pipe and a Book, ca. 1645, where a man, holding an open book, similarly leans out of an open window and stares at the viewer (fig 2). In each work, moreover, the artist has provided textual information on an object illusionistically nailed to the architecture surrounding the window opening: Dou inscribed his signature on a piece of paper nailed to the stone frame, while Metsu identified the man’s profession and date on the wooden board.

The subject of a notary or lawyer appears occasionally in Dutch genre paintings of the seventeenth century, but most of these works are somewhat comical in character. Rooted in a tradition stretching back to mid-sixteenth-century peasant scenes, they depict arrogant lawyers cheating their gullible rural clients.4 Other paintings, including a number of works by Adriaen van Ostade (1610–85) from the end of his career, portray lawyers and notaries in a more dignified manner, often studying documents alone in their offices.5 Metsu also rendered his notary respectably, but in a different manner, almost as though he were soliciting business from the window of his office.

Whether or not Metsu portrayed an actual individual is not known; however, he did have a personal relationship with a notary in the early 1650s. In January 1654 the young artist asked the notary Jan Jansz van Griecken to relieve his guardians of responsibilities that had been given them after his mother’s death in 1651.6 The fact that Van Griecken’s father, a renowned goldsmith in Leiden, owned one of the artist’s works indicates that the notary’s family collected Metsu’s work. The painting in question, “a large picture by Metsu,” which was listed in the father’s posthumous inventory, was in all likelihood also from the early years of Metsu’s career, either one of his sizable history paintings, such as Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (see (fig 1)), or a large genre scene, such as Woman Selling Game from a Stall (GM-114).7 However, Public Notary could not have been a portrait of Jan Jansz van Griecken, as the notary was too young to be the individual represented in this painting.8