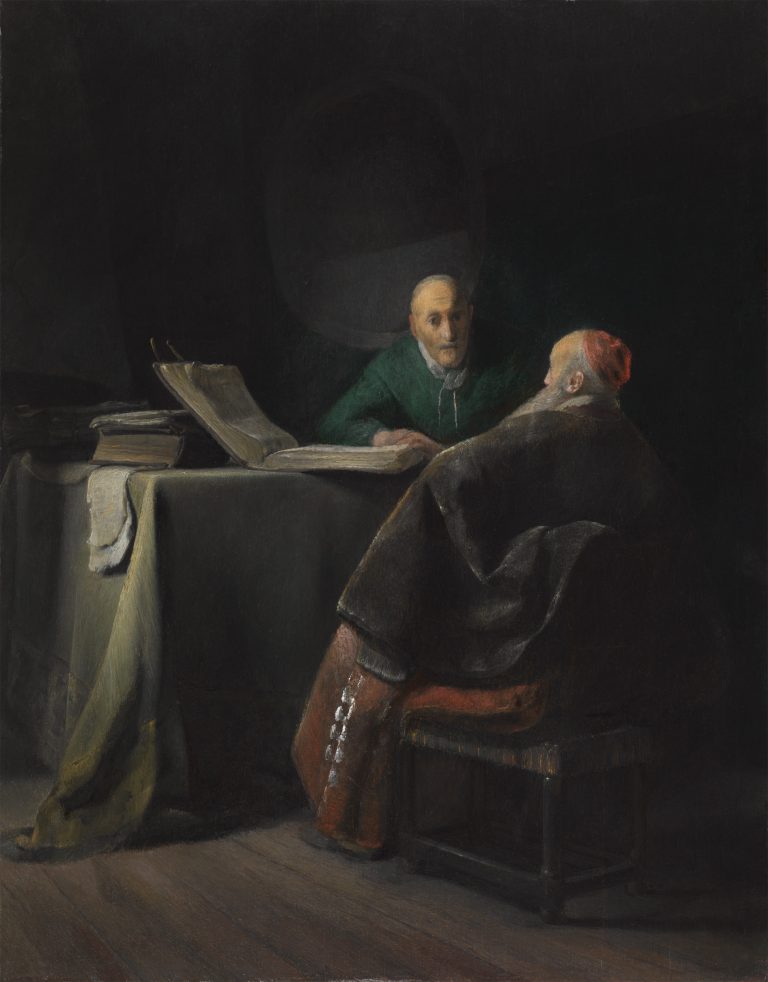

Resting his hands on the large tome lying open on the table, an elderly man leans toward his bearded companion across the table. Diffuse light streaming in from the left catches books and papers at the corner of the table before illuminating the figures’ faces. The rest of the room remains shrouded in relative darkness. The bearded man whose back is turned to the viewer wears a bright red skullcap and a voluminous red robe with silver decorations beneath his heavy dark cloak, attributes that recall the wardrobe of a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.1 Yet, given the suppression of Roman Catholicism in the Dutch Republic during the early seventeenth century (when this painting was executed), it is unlikely that the scene actually represents a theological exchange from those years. A far more likely scenario is that this is a history painting, evoking an imagined discussion between two elderly churchmen from another time and place.

Most probably, the scene focuses upon the fundamental theological dispute between the apostles Peter and Paul that occurred during the second of their two meetings, which took place in Antioch around the middle of the first century AD.2 As described in Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, Paul disputed Peter’s position that Gentile (pagan, non-Jewish) converts to Christianity had to comply fully with the laws of the Torah in order to obtain redemption. Peter’s position was that all converts had to follow Jewish dietary laws and that male converts had to be circumcised, while Paul argued that a non-Jewish convert’s faith in Christ alone was sufficient.3

The theological dispute between these two giants of early Christianity over the proper practices of the faithful had great resonance in the Dutch Republic of the 1620s, a period of acrimonious tensions between the moderate Remonstrant and hard-line Counter-Remonstrant factions within the Dutch Calvinist community. One aspect of that controversy concerned the appropriate level of religious tolerance that should be extended to those who practiced faiths other than strict Calvinism. This debate not only echoed the issues discussed by Peter and Paul in Antioch, but the way Dutch theologians framed their arguments may also have had an impact on the composition of this painting. Specifically, in his influential Vrye godes-dienst (Free Religion), published in 1627, Simon Episcopius, one of the leading Dutch proponents of religious tolerance, constructed his arguments about the benefits of religious pluralism in the form of a dispute between two men.4

The likely visual prototype for this work was Rembrandt van Rijn’s (1606–69) Two Scholars Disputing (also called St. Peter and St. Paul), 1628, in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (fig 1).5 Not only are the paintings similar in theme and composition, but the man wearing the skullcap in the Leiden Collection painting also echoes—albeit in reverse—the triangular monumentality of the foreground figure in the Melbourne painting.6 The similarities between these works indicate that this painting was also executed in Leiden in the late 1620s, but the artist’s identity still remains in doubt.

The attribution of Two Old Men Disputing has, in fact, confounded scholars for generations. The painting has variously been attributed to Rembrandt; Jan Lievens (1607–74); “a follower of Rembrandt, possibly Lievens;” the “immediate circle around Rembrandt, or even more likely, that of Jan Lievens;” and in 2005 it entered The Leiden Collection as “attributed to Gerrit Dou.”7 This level of uncertainty dates to the painting’s earliest appearance in the literature. When Two Old Men Disputing was sold in Paris in 1787, it was attributed to Rembrandt, but it was sold as a work by Lievens when it changed hands the following year. Over one hundred years later, the Duke of Westminster sold it once again as a work by Rembrandt, an attribution that was maintained for the greater part of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.8 By 1980, however, attribution questions resurfaced and the painting was sold as by a “follower of Rembrandt, possibly Lievens.”

In 1982, the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP) called the painting an eighteenth-century “imitation of Rembrandt’s early style, which was not produced in his own circle.”9 In 2005, however, the RRP reassessed the painting’s attribution and described it as being from the “School of Rembrandt,” proposing that it had “originated in the immediate circle around Rembrandt, or even more likely, that of Jan Lievens.”10 Whoever the artist, an attribution to Rembrandt cannot be supported: in contrast to Rembrandt’s strong chiaroscuro and balanced and vibrant composition, this mirrored adaptation, with the unseen light source bouncing off the vellum pages and the folds of the tablecloth, is more stilted, more sparse, and more somber, and the figures are not modeled with the forceful three-dimensionality so characteristic of Rembrandt.

The painting has more connections to Jan Lievens’s manner than to that of Gerrit Dou.11 A close point of reference is A Magus at a Table, ca. 1631–32, by Lievens in Upton House, Warwickshire (fig 2).12 Both works include dramatically dark backgrounds that accentuate the otherwise evenly distributed light’s focus on the figures and the corner of the table, which has documents dangling over the edge of a heavy, green tablecloth. The delicate handling and the figural types in the painting also seem to echo Lievens’s manner. Despite the uncertainty regarding the painting’s authorship, Two Old Men Disputing fits comfortably within the vibrant artistic environment of Leiden in the late 1620s.