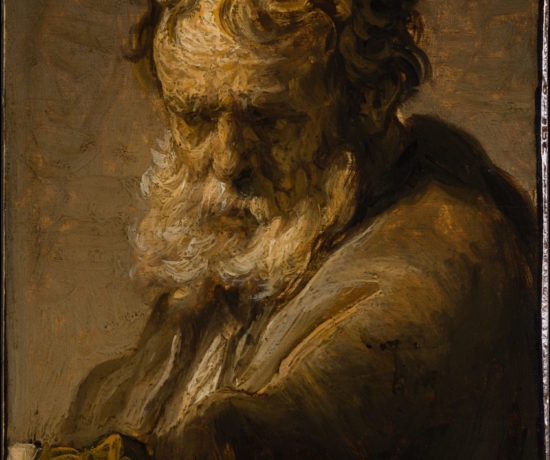

Situated close to the picture plane, head turned sharply and eyes cast downward, the elderly man depicted in Rembrandt’s small, monochromatic oil sketch pulsates with life. With his lips slightly parted and his body seeming to rise with a passing breath, he occupies a world that is nearly the viewer’s own. Rembrandt’s vigorous brushstrokes animate the sitter’s psychological being and physical presence, making this bust-length image seem far larger than it is in reality. Light streaming in from the upper left falls on the right side of the elderly man’s face and models his three-dimensional form. His eyes are open and alert as they focus intensely upon something beyond the composition. Rembrandt emphasized the sitter’s emotional energy through the rhythmic interplay of grays and browns, adding ocher and white accents that appear on the subject’s wiry beard and the curly hair tumbling over his forehead. Both delicate and powerful, Bust of a Bearded Old Man encapsulates the profound humanity of Rembrandt’s finest works.

Bust of a Bearded Old Man is Rembrandt’s smallest known painting, and the only grisaille by the artist in private hands.1 The deep resonance it carries for the beholder arises from an extraordinary paradox: its size—it fits in the palm of one’s hand—belies its monumentality. As Wilhelm Martin, who was then director of the Mauritshuis, noted in 1923, all of Rembrandt’s “prodigious virtuosity” is found in the power of the bearded man’s face.2 The painting was at that point in the collection of Baron Leon Janssen in Brussels, but Martin would not forget it, and when the painting was auctioned in 1927 after the Baron’s death, the Mauritshuis actively sought to acquire it. The museum, however, was outbid by Knoedler’s, which immediately offered the painting to Andrew W. Mellon, noting in its letter to Mellon, “This is considered by the greatest connoisseurs of Rembrandt as one of his greatest gems.”3

Rembrandt’s interest in depicting the physical and psychological character of aging men and women emerged in the late 1620s, when he was a young artist in Leiden, and continued unabated throughout his life. The elderly, whether family members, models in his studio, or random figures he encountered conversing on street corners, clearly fascinated Rembrandt for their expressive physical qualities and underlying humanity.4 He made individual character studies, or tronies, of the elderly in drawings, etchings, and paintings, and these works often served as inspiration for figures in his biblical and mythological scenes.5

Rembrandt painted Bust of a Bearded Old Man in 1633, shortly after he had settled in Amsterdam, revisiting—and in many ways reinventing—a figural type that had preoccupied him when he was in Leiden. In a group of drawings and etchings that he executed in 1630 and 1631, Rembrandt depicted an elderly man with a thick, wiry beard, large forehead, and distinctive features.6 A core image from this group is a red-chalk drawing of the figure seen full length and gazing downward as he sits in an armchair with hands folded in his lap (fig 1).7 The drawing is a masterly depiction of mood, not only because of the elderly man’s reflective pose but also because of the strong contrasts of light and shade that play out in rich variations of red chalk. The related etchings that Rembrandt made in 1630–31 are bust-length images that focus on the bearded man’s head and upper body (fig 2).8 In each of these etchings, Rembrandt subtly varied the man’s pose by changing the angle of his head and altering the length and texture of his beard. The loose and fluid lines of the etching needle enhance the plasticity of the figure. Most importantly, Rembrandt adjusted the intensity and focus of his chiaroscuro effects to convey a different psychological state of mind in each of the etchings.9

Bust of a Bearded Old Man transcends Rembrandt’s depictions of the elderly man seen in the earlier etchings. Boldly executed, the figure in this oil sketch fills the composition, his darkened forearm extending beyond the picture plane. The man’s physical appearance is also somewhat different, as curly hair now falls over his wrinkled forehead, visually evoking his active mind and emotional energy. Rembrandt created this tronie with great assuredness and seeming speed, laying out the entire composition alla prima and making no changes during the painting process.10 He exploited the physical characteristics of paint, oscillating between controlled refinement and loose, textured bravura. For example, while thick, fluid strokes define the man’s sleeve, the ground layer remains visible in other parts of his robe and hair. It is unlikely, however, that Rembrandt painted this image directly from life (naar het leven). His adaptation of a figural motif developed in Leiden suggests that he rendered it uit den gheest, or from his imagination, nevertheless imbuing it with the sensitivity and immediacy of a life study.11

Scholars have consistently remarked on the extraordinary character of Bust of a Bearded Old Man, although the small size of this grisaille oil sketch and its unusual support—paper mounted on panel—have elicited a number of differing opinions about its original function.12 In 1968, Horst Gerson suggested that the painting represented “a fragment of a grisaille sketch,” but the integrity of the composition as a whole and its “self-contained” nature argue otherwise.13 The bold black lines that surround the composition, which act as a kind of framing device, as well as the brushstrokes that extend confidently along the edges of the paper, indicate that the painting has not been reduced in size.14

In the 1980s, Bob Haak and Josua Bruyn, members of the Rembrandt Research Project, suggested that, because of its size and paper support, Bust of a Bearded Old Man may have been intended as a preparatory oil sketch, or modello, for an etching or engraving.15 The limited tones of blacks, whites, and grays in grisaille were beneficial for working out the design of a print, particularly in the depiction of light and shadow.16 Artists and printmakers employed this practice regularly in the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Rembrandt himself used it on at least one occasion. The Ecce Homo from 1634 (fig 3), which he executed in grisaille, was transferred directly onto an etching plate.17 Rembrandt produced several other grisaille sketches in the mid-1630s, including Joseph Telling His Dreams, 1634 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), but it is unclear whether they were also designs intended for prints, as no corresponding etchings for any of them survive.18 The narrative subject matter, multifigural composition, and coarse handling of these grisailles, however, share little with the character of Bust of a Bearded Old Man, whose powerful ability to move the viewer—in its painterly technique and emotional spirit—suggests that Rembrandt intended it as an independent work of art.19

Haak and Bruyn also proposed that Rembrandt may have painted Bust of a Bearded Old Man for an album amicorum, or friendship album.20 They suggested that this context could explain the painting’s large signature and date, and paper support.21 Their point of reference was a pen-and-wash drawing of an old man that Rembrandt executed for the Album amicorum II van Burchard Grossmann in 1634 (fig 4).22 Depicted half length and in three-quarter view, the drawing of a bearded man, with his head turned and his left arm placed prominently in the foreground, bears a number of similarities to Bust of a Bearded Old Man. Yet this delicate drawing, which is accompanied by a moralizing inscription, has an entirely different character than the oil sketch in The Leiden Collection.23 Moreover, as Albert Blankert has rightly argued, the physical character of an oil painting, particularly in a work painted with this rich impasto, makes it unlikely that it was intended for the pages of an album amicorum.24

The confident, self-contained nature of Bust of a Bearded Old Man argues strongly that Rembrandt painted this remarkable oil sketch as an independent work of art. Intimately connected to his ongoing interest in depicting reflective, elderly men, the painting is one of Rembrandt’s most compelling explorations of the physical and psychological character of such figures. By executing this study in grisaille, Rembrandt captured subtleties of form, light, and shade in unparalleled ways, evoking the inner life and individuality of this expressive sitter. Bust of a Bearded Old Man is exceptional for its visual power and masterly technique, and for the way it allows the viewer to look closely and reflect deeply about the human emotions so poignantly captured in this small masterpiece.

Bust of a Bearded Old Man carries an illustrious provenance that stretches back to the late eighteenth century. One of its most important owners was Andrew W. Mellon, who acquired the painting from Knoedler’s in 1928, and it immediately became one of the jewels of his collection.25 Mellon had a special velvet-encased travel box made for the painting, which still exists (fig 5). It is rumored that he carried the work with him everywhere he went and otherwise displayed it on his desk. Bust of a Bearded Old Man captivated the present collector over fifteen years ago when he first saw it in an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,26 and, like Wilhelm Martin, he never forgot it. He was finally able to acquire it in 2018, and this small gem is now one of the pinnacles of The Leiden Collection’s extensive assemblage of works by Rembrandt.